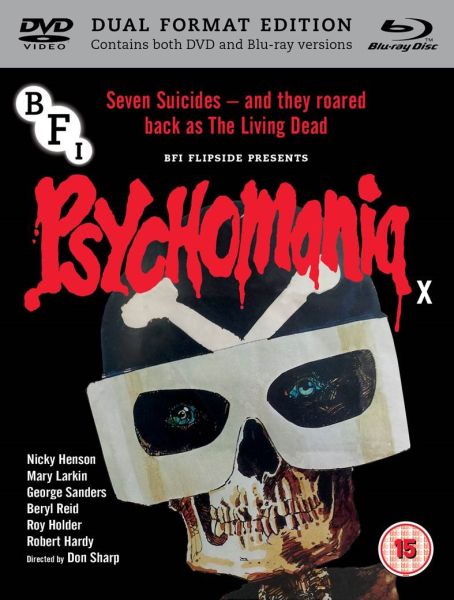

Psychomania (1973) isn’t like any other biker movie I’ve seen. The biker movie genre, in my mind, is quintessentially America, whether it be in youth exploitation movies about vicious cycle gangs such as Al Adamson’s Satan’s Sadists (1969), counter-cultural classics like Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider (1969), or movies which straddle the divide such as Roger Corman’s The Wild Angels (1966). British biker movies are much less prevalent – the only examples I can think of are The Damned (1963), in which the bikers stumble into a military experiment, and Quadrophenia (1979), a period piece dramatising the conflict between the Mods and Rockers in 1964, loosely inspired by The Who’s 1973 rock opera concept album of the same name. But where the bikers of those two films are firmly rooted in a recognisable reality, the cycle gang in Psychomania is something else entirely.

We first meet our bikers in a striking opening sequence as they drive widdershins in slow motion around a stone circle in Avebury, shrouded by the early morning mist, accompanied by psych rock guitar. It’s a beautifully evocative sequence which stirs up decidedly mixed feelings in me as I feel very protective about the preservation of stone circles and can’t help but wonder about damage to the site… but it sure does look good. It doesn’t take very long after this for Tom (Nicky Henson), the leader of the gang (dramatically named The Living Dead), to take offence at a motorist who somehow failed to show proper respect and to drive him off the road with the eager assistance of red-leather-jacketed Jane (Ann Michelle). The only other female member of the gang is Tom’s girlfriend Abby (Mary Larkin), whose preference for blue corduroy over black leather marks her out as the nice one. Most of the other male gang members have either made up their own names or had very odd parents: Bertram (Roy Holder); Hatchet (Denis Gilmore); Chopped Meat (Miles Greenwood); Gash (Peter Whitting); and Hinky (Rocky Taylor). Rather helpfully, each of the gang members has their name embroidered in large, colourful letters on the left breasts of their leather jackets, which must come in very handy for the police whenever they receive reports of the gang’s depredations. (Not that the police seem particularly useful – despite knowing the identities of all the gang members, there’s no indication that they’ve ever even attempted to arrest a single one of them before the film begins.)

The members of The Living Dead are a thoroughly middle class lot who still live with their parents. Their leader Tom is very much the child of privilege – he lives in a large country house with his mother (Beryl Reid) and her manservant Shadwell (George Sanders). Mrs Latham hosts spiritualist meetings and conducts seances, but rather than being a charlatan living off ill-gotten gains, she charges no money for her sittings and appears to be genuinely talented. Shadwell is a rather more mysterious figure who looks after her and tends to her needs, but is treated by her as an equal or even (in some ways) a superior. Oh, and apparently he hasn’t aged a day as long as Tom has known him. Inquiring into the mysterious death of his father from unknown causes in a locked room, which is somehow connected to mysterious secrets of post-mortem survival, Tom convinces his mother and Shadwell to give him the key. Protected by an amulet depicting a toad, Tom undergoes some sort of cryptic occult trial/vision quest experience which provides hints to aspects of his past but doesn’t provide the answer to his burning question. This is inadvertently provided by his mother’s conversation with Shadwell while waiting for him to regain consciousness – apparently all it takes to survive death is to believe you’ll survive (his father had last minute doubts). Excited, Tom promptly drives his motorbike off a bridge.

Abby, who was with him at the time, reluctantly admits to his unfazed mother that it was suicide. She asks permission for the gang to bury him “their way”, to which his mother readily agrees. You might not think that a small motorcycle gang in a small English town who’ve just experienced their first fatality would have a traditional method of honouring their dead, but you’d be wrong. They bury Tom sitting on his bike, dressed in his full regalia, posed in a manner not exactly representative of the way most corpses would behave without considerable assistance. The funeral song is a jaw-droppingly inappropriate hippy folk anthem about a biker who just wanted to live free on the road but the oppressive culture of The Man led him to choose death in preference, eulogising an anonymous death mourned only by The Chosen Few who knew him. Musically it’s a desperately misguided choice, something you’d expect the gang to mock rather than willingly listen to, and the lyrics describe a gentle soul who just wanted to live his own life, somebody who has nothing in common with the bored thug that we’ve seen – which might have been an intentional choice on the part of the filmmakers, but I suspect this was a production decision made without the involvement of the director or writers. The pretty young hippy boy miming the song stands out like a sore thumb among the gang members and strums the guitar when he should be picking at it. Compared to this, Shadwell’s brief appearance to deposit the toad amulet in Tom’s grave and tip his hat to the mourners seems almost normal.

Presumably our deceased biker likes an audience, because it’s not until a stranded motorist (Roy Evans) takes a shortcut across the stone circle in the middle of the day that Tom erupts from the grave on his motorcycle (very impressively staged), pausing only to run him down before going on to murder a petrol attendant and several pub customers. He then lets the rest of the gang in on his secret, prompting a series of spectacular suicides which occasionally verge on the farcical, such as the guy in his speedos who staggers to the side of a river and throws himself in while chained to a bunch of weights. My favourite is the guy who left his bike in a clearly marked “no parking” zone. He lurks inside a 14th story apartment waiting for a policeman to turn up and yell for him to come down, allowing him to surprise the relevant authorities by taking the direct route from window to pavement. It’s rare to see that level of dedication in a practical joke.

One of the suicides fails to return, but the others set out to enjoy their new existences as immortal super-strong undead bikers who can tear apart prison bars and drive unharmed through brick walls (raising the question of whether their bikes are also immortal). Only Anne – whose attempted suicide by sleeping pills failed, resulting in nothing more than a series of anxiety hallucinations – is determined to hang onto life. While Chief Inspector Hesseltine (Robert Hardy) enlists her cooperation as bait in order to arrest the gang, Mrs Latham has become increasingly disturbed by her son’s willingness to share the secret of immortality with his friends. His stated intention to work his way through the country murdering everybody who’s part of The Establishment leads her to enlist Shadwell’s assistance in bringing an end to their depredations – but will Tom manage to take Anne with him first?

Tasmanian Don Sharp is a director with solid credentials when it comes to action and stunt work, having been responsible for the action sequences in Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines (1965) and the Alistair MacLean adaptation Puppet on a Chain (1971). He directed the Hammer Films productions Kiss of the Vampire (1964), The Devil-Ship Pirates (1964) and Rasputin: The Mad Monk (1966), but by this point Hammer’s influence was on the wane, while Sharp’s overall career trajectory took him away from horror and more into the action thriller mode. He pulls off a great range of vehicular stunts here, helped no end by having access to an extensive stretch of curving roads which hadn’t yet been formally opened to the public. Award-winning director of photography Ted Moore adds an extra touch of class to proceedings. His CV includes seven out of the first nine James Bond films (1962-1974), as well as the final three Ray Harryhausen productions (1973-1981). The film’s screenplay was the second and final collaboration of Arnaud d’Usseau & Julian Halevy, who were responsible for the delightful nonsense that was Horror Express (1972) (reviewed here). This screenplay is far less coherent than their first, failing to explain many of the details behind their own scenario, but I think it adds to the movie’s overall charm – it’s hard to imagine it being as much fun if every little plot detail had been nailed firmly down.

The cast is surprisingly strong for an obscure low budget British horror filmed in 1971. Nicky Henson (Witchfinder General) took the job as biker gang leader to supplement his income while performing Shakespeare in the evenings. He takes the role seriously, setting the tone for the rest of the gang and providing a solid spine on which to hang the film. He’d later turn up as Demetrius in the BBC Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1981). Roy Holder (The Virgin Soliders) has also done his fair share of Shakespeare – Othello (1965), The Taming of the Shrew (1967), Romeo and Juliet (1968) – and was one of the series regulars in Ace of Wands (1972) around this time. Rocky Taylor is a stunt performer with an extensive career, including 12 James Bond films (1962-1999) and 3 Indiana Jones films (1981-1989). Robert Hardy (the police inspector) had played Henry V in An Age of Kings (1960) but is probably best remembered as Siegfried in All Creatures Great and Small (1978-1990). A really thorough trawl through the various cast members’ credits would reveal a series of parts scattered throughout classic British TV and cinema (both prestige and cult), from Doctor Who to Jane Austen. But the unquestioned stars of the film, who earn their billing at the head of the credits, are George Sanders and Beryl Reid. Beryl Reid is probably best known as a comedy performer – she had recently parodied conservative activist Mary Whitehouse in The Goodies: Sex and Violence (1971) – but she’s equally adept as a dramatic actor and never mocks the material she’s given here (much as she might have been tempted). The on-screen bond she has with Nicky Henson (playing her son) is a vital component in selling their central family dynamic. Even so, she’s overshadowed by George Sanders in his final screen performance, bringing all of the charm and poise of a career spent mostly playing smooth-talking cads – a career, sad to say, which has largely passed me by. Apart from a few scattered earlier roles – Hitchcock’s Rebecca (1940), The Ghost and Mrs. Muir (1947) – I’m most familiar with his 1960s work, from the Disney movie In Search of the Castaways (1962) through the Pink Panther series entry A Shot in the Dark (1964) to The Man from U.N.C.L.E. (1965), Batman (1966) and The Jungle Book (1967). In fact, come to think of it, Psychomania is the first film I’ve seen him in which I didn’t first encounter during my primary school years. Despite the unfounded rumours that his suicide (which occurred shortly after making this film) was a reaction to seeing a rough cut of the movie, he appears to have had a great time on set and he dominates the material with ease – if this had to be his final work, it’s a pretty good way to go out.

BFI Flipside assembled an interesting selection of short films to accompany their Blu Ray release. Discovering Britain with John Betjeman: Avebury, Wiltshire (1955) is a 3 minute B&W mini travel guide for British motorists, one of a series of 26 short films sponsored by Shell-Mex Petrol and narrated by poet Betjeman. It provides an opportunity to glimpse more of Avebury’s stones and teases potential visitors with its “sinister atmosphere.” There are even some sample tourists on hand, presumably to model appropriate “visiting the local sights” behaviour.

Roger Wonders Why (1965) is a weird little glimpse into the conservative England of the mid-1960s, a desperately amateurish production put together by a church youth group from Chelmsford. Roger is the narrator and “star” of the piece, taking us into the world of the Saint Andrew Young Communicants Fellowship and their wacky nights of fun forming a conga line and jumping up and down. There’s a strange new visitor in a leather jacket who doesn’t fit in, so Roger goes over to talk to him. This is Derek, a Rocker, who’s also a member of The 59 Club, a motorcycle enthusiast social venue run by fellow biker the Reverend Bill Shergold (who remained the club’s president from its foundation in 1962 until his death in 2009). Luckily Derek happens to be carrying a complete second set of Rocker gear in Roger’s size. One shoddily edited quick change later, they’re off at The 59 Club visiting the Reverend, who doesn’t pressure club members to attend church but is a strong advocate of respecting other drivers and using motorcycles “to the glory of God”. Inspired to continue his new life as a biker, Roger stops to help a fellow motorcyclist who has broken down and follows him to an exciting meeting with a group of venture scouts. After some rope play and abseiling, Roger shoehorns in some heavy-handed messaging about how these activities make him think of his faith in God, before finally returning to his youth group to share his experiences (while continuing to wear his new leather gear – which, come to think of it, was only intended to be a loan, which leaves some awkward unanswered questions about Derek). It’s hopelessly lacking in quality of concept or execution, but as an authentic social document it has its interest.