Roger Corman’s New World Pictures, churning out low-budget B-movies for international distribution from 1970-1984, also acted as a training ground for up-and-coming filmmakers such as Jonathan Demme and Ron Howard, providing a crash course in how to make a movie with minimal resources to a tight schedule (although whether you were always fortunate enough to be paid for the experience is a matter of some contention). Piranha (1978) and its independently-produced sequel Piranha II: The Spawning (1982) launched the careers of renowned directors Joe Dante (Gremlins, Innerspace, Small Soldiers) and James Cameron (The Terminator, Aliens, Titanic) respectively.

Joe Dante’s first film was The Movie Orgy (1968), a 7½ hour mashup of film clips and commercials made during his student days. His skill as an editor was used to great effect in cutting together trailers for the output of New World Pictures, displaying his talent for cobbling together the best moments from each movie (and, occasionally, footage from other movies) to make them look better than they were. After collaborating with Allan Arkush to make Hollywood Boulevard (1976), a budget-saving compilation of footage from other New World movies stitched together within a framing story about an actress starting her career in low-budget movies, Joe Dante made his solo feature debut with Piranha.

Piranha was consciously conceived as a Jaws ripoff, but where Jaws went big with its giant shark, Piranha went small. Taking the basic concept from Richard Robinson (Kingdom of the Spiders), Corman handed the script off to up-and-coming writer John Sayles, whose debut novel Pride of the Bimbos (1975) (which I gather is classier than its title suggests) was sufficiently impressive that he was hired for his first screenplay without the need to provide a writing sample. After turning in his script about genetically modified piranha bred for intelligence and survival in a range of environments as an abortive Vietnam War experiment (interwoven with social and political satire), Sayles would continue to produce low-budget B-movie scripts well into the 1980s as a way of funding his own more serious projects as a writer/director (Return of the Secaucus 7, City of Hope, Passion Fish).

Skiptracer Maggie McKeown (Heather Menzies) (first seen on screen playing the unlicensed Jaws ripoff Atari videogame Shark Jaws) travels to Lost River Lake, Texas, in search of two missing teenagers and channels her Tigger-energy to bounce alcoholic curmudgeon Paul Grogan (Bradford Dillman) into acting as her local guide. A trip up the mountain to the local abandoned military research base leads to the discovery of the teenagers’ belongings near the body of water in which they took their ill-advised topless midnight swim. An investigation of the laboratory reveals a number of abandoned experiments, including a gratuitous but delightful stop-motion creature which is a clear homage to Ymir from Ray Harryhausen’s 20 Million Miles to Earth (1957). Determining that draining the pool would be the quickest way to find the teenagers’ bodies, they are attacked by a panicked man (Kevin McCarthy) with a boathook, successfully fending him off only for him to escape and crash their car. Upon regaining consciousness he reveals that he is Dr. Robert Hoak, a scientist who worked on the abandoned experiment, and that they have just dumped hundreds of mutant piranhas into the local river system. Without a car, they are forced to travel downriver on a raft in an effort to prevent the piranhas from attacking the local children’s summer camp and the new water park resort, hampered by encounters with the military and a Mayor who refuses to heed their warnings.

The cast is surprisingly solid for a film of this type, completely lacking in any of the embarrassingly wooden performances or poor line-readings which would normally at least make an appearance among the supporting players. Bradford Dillman (The Iceman Cometh) and Heather Menzies (The Sound of Music) play well off each other, despite not being completely convincing as a romantic pairing, and are ably supported by cameos from seasoned character actors Keenan Wynn (Colonel Bat Guano in Dr. Strangelove) and Richard Deacon (Invasion of the Body Snatchers). Corman regular Dick Miller puts in a comic turn as local Mayor Buck Gardner in the second of many roles in Dante’s films. Writer/director Paul Bartel plays the self-important owner of the summer camp, a minor bully who ultimately puts himself at risk to save the children in his care. Belinda Bulaski (another Dante regular) and Melody Thomas (shortly before beginning an ongoing role in The Young and the Restless) are more likeable than many camp counsellors in low-budget horror movies, and Shannon Collins is charming as Paul’s daughter, one of that rare breed of child actors who are capable of both acting and not being annoying. Kevin McCarthy (Invasion of the Body Snatchers) and Barbara Steele (a genre legend due to her appearance in Italian Gothics such as Black Sunday [La maschera del demonio]) turn up in small roles to provide genre cred, and screenwriter John Sayles makes a cameo as an army sentry in a scene which provides a good-humoured excuse for gratuitous naked breasts (obligatory for movies of this type, but sparingly used here).

Joe Dante manages to do a lot with the resources available, using careful editing to create the illusion that his piranha models can do more than they’re actually capable of. Sparing use of Rob Bottin’s special makeup effects in combination with clouds of red in the water conveys the bloody impact of the piranhas without going overboard. The score by Pino Donaggio (frequent collaborator of Brian de Palma) isn’t one of his strongest, but it does the job.

Piranha was one of New World Pictures’ biggest financial successes, released on the heels of Jaws 2 (1978) and finding an early champion in Steven Spielberg. I first encountered it on TV in my early teens, at a time when my best opportunity for a Friday night out was to attend the local Christian youth group. Bizarrely, the youth group leader at that time would occasionally host backyard barbecues accompanied by whatever genre movie happened to be airing on TV that night (which I would never have been allowed to watch at home). I always spent more time watching the movie than running around outside with the others, and have fond memories of being introduced to both Piranha and David Cronenberg’s Scanners (1981) in this atypical setting. Some thirty years down the track, Piranha stands up surprisingly well and I’d happily recommend it.

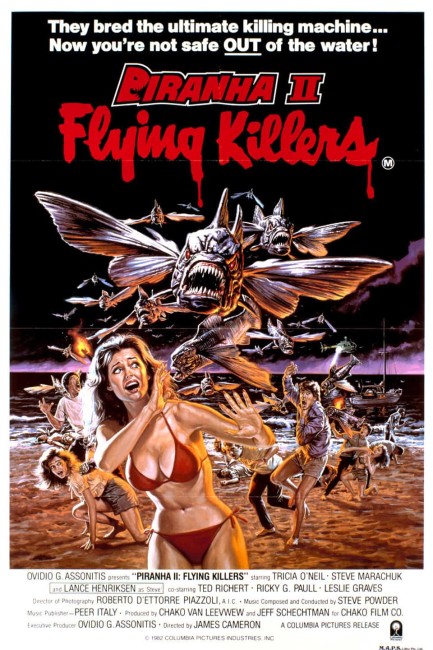

In the aftermath of Piranha‘s success, two of New World’s producers purchased the sequel rights and set up their own independent production company, securing financing from Greco-Italian filmmaker Ovidio G. Assonitis (director of the octopoid Jaws ripoff Tentacles [Tentacoli]). Having commissioned a screenplay from Piranha‘s assistant director Charles H. Eglee, they brought in Joe Dante’s trailer-editing colleague Miller Drake to direct. James Cameron had been working for New World on production design and special effects photography, in addition to providing matte paintings for John Carpenter’s Escape from New York (1981), and was assigned to the picture as special effects director. Assonitis fired Drake before shooting began and Cameron was promoted to his first job as director.

In Piranha II: The Spawning (more excitingly titled Piranha II: Flying Killers for the international market), the scene has shifted from Texas to a Caribbean island resort, unfortunately located in the vicinity of a sunken shipwreck containing a lost cylinder of piranha from the previous movie’s research project – except this batch have wings. After the deaths of a pair of divers who decided that the seabed next to this wreck was a great place to have sex, diving instructor Anne Kimbrough (Tricia O’Neill) breaks into the morgue to see whether she can identify the sealife which killed them, having been denied access to the corpses by police officer Steve Kimbrough (Lance Henriksen), her estranged husband. Accompanying Anne is Tyler Sherman (Steve Marachuk), one of her diving students who’s been trying to get into her pants while secretly looking for the missing canister after quitting the military research team responsible. The morgue attendant discovers them and kicks them out, only to be killed by a piranha launching itself from inside one of the corpses, and the bodycount clock commences its countdown.

The three actors in the preceding paragraph represent the full extent of anything resembling acting talent on display – the rest of the cast range from uninspired to dire. Horny 16-year-old Ricky G. Paull makes some particularly bizarre choices as the Kimbroughs’ son, as in the early scenes with his scantily clad mother (barely covered by a sheet before putting on a short dressing gown) it looks like he’s coming on to her. Where Piranha paid cheeky lip service to the commercial imperative of putting breasts on display, Piranha II opts for leering at them instead, exploiting any opportunity it can get to remove the clothing of actresses cast for their photographic experience rather than their acting. Even Tricia O’Neill has to submit to lingering shots of her sleeping form, although she’s at least allowed to keep her assets offscreen. And the ramped up gore effects for the piranha attacks just look tacky – where Piranha made a lot out of relatively little, Piranha II has gone the other way. Stelvio Cipriani, who contributed many notable scores to Italian horror movies during the 1970s, at least provides a solid framework for the movie to play out in, but it’s not one of his more inspired scores and is still rooted musically in the previous decade.

How much of this can be laid at James Cameron’s door is difficult to say. Although Cameron was responsible for the filming, many of the creative choices were dictated by Assonitis and Cameron was excluded from the editing room. According to his biography Dreaming Aloud, Cameron broke into the editing room to re-cut the movie while the producers were absent, but Assonitis was responsible for the final release cut. Although the underwater sequences are some of the more effective in the film and look forward to his later passion project The Abyss (1989), it’s not difficult to see why Cameron left this movie off his CV for years. Similarly, Charles H. Eglee’s screenwriting debut is hardly an auspicious beginning – this is not the work of a writer you would expect to see working on Moonlighting (1985-1989) just a few years later. Eglee would work with Cameron again in the future, co-creating the SF TV series Dark Angel (2000-2002) and receiving story credit for Terminator: Dark Fate (2019). Miller Drake, Piranha II‘s original director, would also work with Cameron again as the visual effects editor on The Abyss, Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991) and True Lies (1994).

Where Piranha is a lot of fun and still holds up today, I cannot in all conscience recommend Piranha II to anybody looking for quality entertainment. Unless you’re intensely interested in seeing Lance Henriksen’s first work with James Cameron, I’d say it’s best reserved for an evening of drunken mockery with friends.